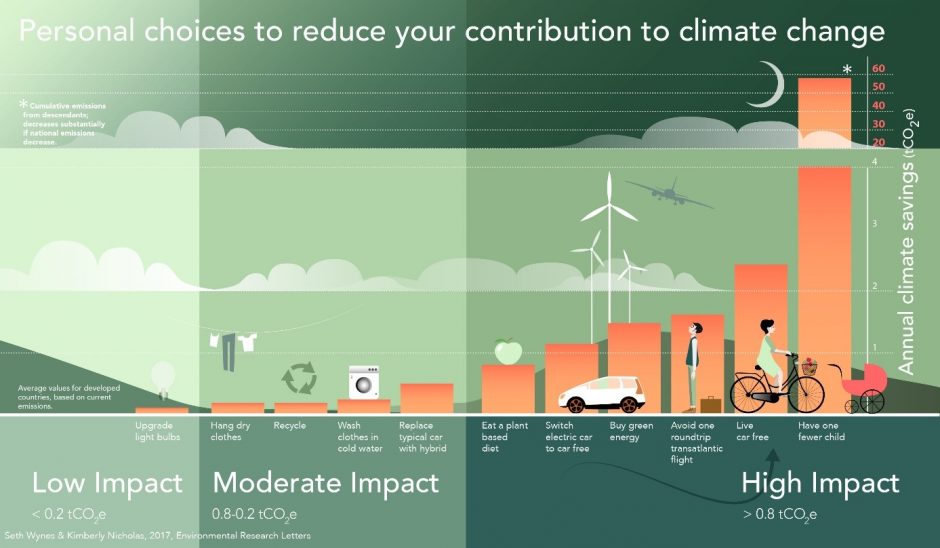

We all have an ecological footprint, but often, we aren’t aware of which of our individual actions has the biggest impact.

Seth Wynes, a former UBC PhD student in environmental geography says that intuitively, we tend to focus on actions that actually make only a small impact our greenhouse gas emissions.

Now a postdoc at Concordia University in Edmonton, Seth studies climate change mitigation, and in past studies made use of a life-cycle assessment approach to quantifying contributions to greenhouse gases. I began reading about Seth’s research a few years ago, when I was trying to figure out how I could reduce my own carbon footprint.

How can individuals contribute to climate action?

Around that time, when I asked others how they thought one could reduce their impact on the environment, they suggested things like using fewer plastic bags when shopping, or turning the lights off when you leave a room.

“Those topics are very mentally accessible, but actually don’t have a big carbon footprint,” Seth told me in an interview.

Dr. Seth Wynes

These are his first-line recommendations:

• eat a plant-based diet

• avoid air travel

• try to live car free

All three require substantial adjustments in our choices as individuals, as we navigate the complexities of working and studying on campus in the midst of the pandemic.

Committing to carbon reduction can start with focusing on just one of these recommendations. As an individual, your biggest cause of emissions depends on your lifestyle.

If you want to dive into finding out more about your individual footprint, there are several tools available online you can use.

Another way to reduce your footprint involves your wallet. Green financing means pursuing an investment strategy that avoids fossil fuel companies and other environmentally damaging businesses.

The same idea applies to green energy: where you can, switch to cleanly generated sources of fuel and power, in the way you heat your home, cook your food, and run your lawn mower.

Diminish the footprint – but maximize your handprint

While it’s great to reduce your own emissions, the effects of those actions are limited in the context of a society that is still based on fossil fuels, according to Seth. The very infrastructure we use—like cars and public buildings—is damaging for the environment.

“It’s very important that we change the structure and the social norms that cause so much pollution,” said Seth. This idea is sometimes called the ‘carbon handprint,’ and summarizes all actions which lie outside of your direct behavior and consumption.

Seth Wynes & Kimberly Nicholas, 2017, Environmental Research Letters

“Contact your member of parliament, vote for politicians with ambitious climate platforms, and join an organization that fights for change,” Seth adds. He recently published a paper in Cell Press’s One Earth where he showed that voting for a conservative party in Canadian elections results in a drastic increase of emissions. Hence, voting is an important part of your handprint.

There are many other options. “We each should find the biggest leaver to pull on and pull on it as hard as we can” Seth says.

The special role of people at UBC and in Vancouver

I always ask my interview subjects how their research topics are related to people in our community, specifically to the UBC community, and the city we call home.

“If you’re studying or working at UBC, there’s a big chance you have, or will have a big influence on the society,” Seth observed. And indeed, UBC researchers are lighting the way: Electrical and Computer Engineering Professor Alireza Nojey, and Vanier scholar Ehsanur Rahman are evaluating ways to harness the heat of the sun to boost solar generation efficiency with thermionics.

In Vancouver, in contrast to other places in Canada, it is possible to live without a car, because public transportation and bike lanes are well established. To further promote this, Seth suggested encouraging the city to densify public transit stations, improve bike infrastructure and make it easier to choose not to drive. Alternative transportation prevents air pollution, decreases road fatalities, and is good for the climate – a win-win-win situation.

This article was written by Dr. Moritz Koch, a postdoctoral fellow in the Department of Microbiology and Immunology working in the Hallam lab. Moritz recently took 1st place speaking about his cynobacteria research in the UBC Postdoctoral Association 3-Minute Postdoc Slam on Aug. 3, 2021.

References

Seth Wynes and Kimberly A Nicholas 2017 Environ. Res. Lett. 12 074024