Productivity, drive, and a penchant for cutting-edge technologies have characterized the career of LSI’s Dr. Don Moerman, Professor Emeritus in the Dept. of Zoology.

We spoke to him about his focus on Caenorhabditis elegans biology and functional genomics, and what it took to engineer the success of the C. elegans Knockout Project, an international consortium created to generate knockouts in every one of the worm’s 20,000 genes. To date, 16,000 genes have putative null alleles, which are available through the C. elegans Genetics Centre (CGC).

Dr. Moerman began his academic career at Simon Fraser University, in Burnaby, B.C. In an interview with his alma mater, he advised students to “follow what interests you, dig deep into it, and ignore the academic silos.” Throughout his career, he has followed his passion for studying C. elegans, dug deep, and persisted by constantly exploring new approaches. We asked him to reflect on his career.

Why C. elegans?

“The first really significant paper on C. elegans was in 1974. I started grad work a year later.”

Dr. Sydney Brenner, co-laureate of the 2002 Nobel Prize in Medicine, had used C. elegans as a model organism to study development. His 1974 paper in Genetics identified about 100 genes, 77 of which, when mutated, affected movement. He had chosen this small roundworm as an ideal model for his work because it was multicellular but not too complex, easy to grow in large numbers, and convenient to manipulate for genetic analyses.

Don pursued his graduate studies with one of Dr. Brenner’s postdocs, Dr. David Baillie, at Simon Fraser University. Don had isolated mutant worms with defects in muscle contraction, which could be explained by mutation of either neural or muscle proteins. He had wanted to do his PhD in neurobiology, but all of the mutants he was interested in turned out to be muscle mutants. He studied the gene unc-22. These mutants had a distinct phenotype: homozygous mutant worms were “uncoordinated” and constantly twitching, while heterozygotes behaved normally on agar but vibrated when placed in a 1% nicotine solution. By studying rare meiotic recombination events, he constructed a detailed recombination map of the unc-22 gene.

Don had also looked for suppressors of unc-22 mutants, mutations in other genes that inhibited twitching. The suppressors Don found were in unc-54, which Dr. Robert Waterston and colleagues had shown encoded the major form of myosin heavy chain in muscle. Don went to Dr. Waterston’s lab in St. Louis to follow up on observations made during his Ph.D. Together, Don and Dr. Waterston mapped Don’s suppressor mutations onto unc-54, and realized they were located in a region encoding the motor activity of the myosin heavy chain. They hypothesized that Don’s mutations inhibited the motor activity of myosin by making it bind more tightly to actin, suppressing the twitching phenotype induced by unc-22 mutations. This work was published in Cell.

Don was recruited to UBC in 1987, as an Assistant Professor in Zoology. After eight years in the Waterston lab, he had a couple of projects in hand, focusing on the study of muscle genes.

“We identified several muscle genes, but we didn’t know what they did,” he said. “Starting my lab, I was pretty focused on UNC-52/Perlecan – a giant extracellular matrix protein – and we published at about the same time as a Finnish group published on the mammalian homolog. Work on Perlecan, which started in Bob’s lab, was really my first big independent work here.” Don’s group has discovered or co-discovered eight genes affecting muscle in C. elegans, and their work has helped explain how these proteins function together in the assembly of the sarcomere.

Director of the C. elegans knockout facility in Vancouver

In May, 1998, as Drs. John Sulston and Robert Waterston were preparing for publication of the complete sequence of the C. elegans genome, Don was invited to a meeting at the Sanger Center. The purpose of the meeting was to discuss the initiation of a project to mutate every single one of the organism’s 20,000 open reading frames, which was only feasible because the worm strains survive freezing. Prior to this, only 700 genes had been identified through mutation in 25 years.

Dr. Waterston commented that beyond his passion for studying muscle, “Don also had a strong sense of how science moves forward from the tools and resources that are generated by some labs.”

Don recalls being excited by the project. “I was invited to this meeting, ironically I was one of two geneticists, the rest were molecular biologists. I liked the people, also a criterium for me. We agreed to all go home and write grants and work as a consortium.” The group faced early hurdles in securing funding. In fact, within the first two years of starting, most labs dropped out.

“I owe a lot to Michael Smith labs,” he added. “Doug Kilburn, he really liked the project – he took it to VP Research, and procured enough funding for one technician and a little bit of equipment for a year, and then we received two years of CIHR seed money.” A small CFI with Dr. Ann Rose and Dr. Terry Snutch also helped fund some of the early infrastructure. With this early support, Don established a world-class facility at UBC, as part of an international consortium that included groups from the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation and the Tokyo Women’s Medical University School of Medicine.

In 2001, he secured a major grant from Genome Canada and found himself on the six o’clock news. “This was the only time I’d ever been on the news. Five projects got funded in B.C. Ours was the one that caught their imagination. It was picked up by Peter Mansbridge on the National.”

In 2001, he secured a major grant from Genome Canada and found himself on the six o’clock news. “This was the only time I’d ever been on the news. Five projects got funded in B.C. Ours was the one that caught their imagination. It was picked up by Peter Mansbridge on the National.”

They worked in lock-step with their American collaborators for the next 10 years. But after two successful rounds of funding, Genome Canada moved on to focus on other projects, concluding the knockout project had done what it was intended to do. Don was undeterred. He wrote to CIHR, with a supporting letter from all six Nobel prize winners in C. elegans. Their application was successful, then didn’t get funded in the next round. But Don persisted, “a real Hail Mary, since we were running on fumes”, and got further support for his project. Don has kept the Vancouver node of the consortium running for the last 20 years.

Looking up at a framed version of the letter signed by the Nobel laureates on his office wall, he remarked, “I used the community to help us get funded. If you have the idea to complete a worm genomics project, you can’t do it halfway, you do it to completion.” To date, the international consortium and the larger worm community has identified deletion and nonsense alleles for over 16,000 genes, all are deposited at the CGC for distribution to the wider research community. Don’s part in the project is currently supported by CIHR and an NIH subcontract, but both grants are due to end in 2021.

“Right now, we have a lot of money, but not for much longer,” he said. “I think I’ve been really lucky…but I think after another year and a half, I’m going to fold up the tent. It’s a shame because right now I have a great team of people in my lab, and CRISPR is working well for us.”

Don attributes their success to how well he and his colleagues have adapted to new technologies to ensure the timely completion of the project. They have changed techniques many times over the years to get all their knockouts out. “We adopted these technologies because we were trying to be more efficient.” The CGC sends out 30,000 strains a year – a third of the strains are from Don’s lab.

Since adopting CRISPR and whole-genome sequencing (WGS), they have made another 500+ knockouts. They uploaded their methods to bioRxiv, and garnered enthusiastic tweets and downloads for valuable insight on CRISPR optimization and quality control in the worm.

“People talked about all this off-target stuff. We built a lookup table database http://genome.sfu.ca/crispr/about.html, you can use it to find a guide RNA that is unique for your gene. Stephane (Flibotte, now lead bioinformatician and bioinformatics core manager at the LSI) built these tables where you can look up the gene, look up sequence specific guide RNAs and use these for CRISPR. As proof of concept we did whole genome sequencing of 30 CRISPR derived deletion strains to check for off-target sites. We found none. You can eliminate that problem if you choose guide RNAs carefully. We published this in G3.”

Don has always been quick to adopt new technologies. He figures he had the first PCR machine at UBC: “funny,” he said, “considering we didn’t work in the Michael Smith labs.” On a trip back to St. Louis, two of Dr. Waterston’s postdocs had shown him their PCR machine. Don’s lab had been cloning and sequencing but didn’t have a way to get short pieces of DNA quickly. He remembers asking why you wouldn’t just grow the DNA in bacteria and cut it out.

“Both postdocs looked at me, like, ‘this guy’s an idiot.’ I left and got on a plane for Vancouver. I get about as far as over the Rockies when the penny dropped, and I realized what PCR could do. I wrote an NSERC equipment grant on the plane.”

He was also quick to adopt new microscopy. “I was always fascinated by the image – I went to Ralf Schnabel’s lab in Germany to do 4D microscopy. I wanted to find out where all the muscle cells came from and where they went.” When a colleague purchased an early model Biorad confocal microscope, Don asked if he could use it to test out a couple of antibodies he had to Perlecan – this image ended up on the cover of Developmental Biology. “We jumped on those technologies. That was probably what I meant when I talked about silos. I was trained as a geneticist, but had to go into biochemistry and cell biology, to answer biological questions.”

An extension of the knockout project was the Million Mutation Project, a large-scale WGS project which allowed him to renew his collaboration with Dr. Waterston, as well as Dr. Jay Shendure in the Department of Genome Sciences at the University of Washington. They have generated and sequenced a library of ~2000 mutagenized isogenic C. elegans strains. The library contains over 800,000 unique single nucleotide variants, and provides the worm community with a valuable source of mutations in almost every gene (http://genome.sfu.ca/mmp/).

Mentoring

Many of Don’s 30 graduate students, postdoctoral fellows, and research associates have moved on to successful careers in academia and industry. He has also trained 58 undergraduates, co-op students and technicians, either in his research lab or in the knockout facility.

Don has also made significant contributions to undergraduate programs at UBC. He was involved in revising Genetics and Developmental Genetics courses, and introduced genomics lectures for these courses. Don has encouraged and inspired his students to do what they’re passionate about. In his classes, he discusses applications for WGS and CRISPR, and talks about bioethics. He recalls one of his third-year students, who had two parents in law but wasn’t interested in following in their footsteps. The student, excited by what Don was teaching on bioethics and law, ended up pursuing law after all.

“That was pretty funny.”

He encourages the students in his lab to be curious and take on projects they’re interested in doing, because he feels “curiosity can get you a lot further than if you’re just smart.” He himself, Don says, was always driven, but was a typical old-school grad student. “I slept in, got in late in the morning, was here all day and half the night. Some people who are 9-5ers would look at people like me and think we’re lazy because the first thing we did was go for coffee. I lived [in the lab] that was my culture, and that was what I did. I was there 7 days a week until I met my wife.”

He encourages the students in his lab to be curious and take on projects they’re interested in doing, because he feels “curiosity can get you a lot further than if you’re just smart.” He himself, Don says, was always driven, but was a typical old-school grad student. “I slept in, got in late in the morning, was here all day and half the night. Some people who are 9-5ers would look at people like me and think we’re lazy because the first thing we did was go for coffee. I lived [in the lab] that was my culture, and that was what I did. I was there 7 days a week until I met my wife.”

Don officially retired at the end of 2019, but will keep his lab open until 2021. He remains passionate, and is generous to his fellow scientists. “Our own list of genes is important to us as we wish to complete certain gene families, but we prioritize requests from the community. We can’t take a year to give them a knockout, we often get knockouts to them in 2 months. If we get requests, they jump the queue over things we have on the list. There are 70 research labs using the worm in Canada. I’m retiring but working for another 18 months. If you want knockouts, get them in the queue.”

In addition to a career of outstanding research, evidenced by more than 125 peer-reviewed publications in top journals and over 8500 citations, Don’s leadership has created a rich legacy of talent and resources, upon which the next generation of scientific discoveries will be built. Dr. Linda Matsuuchi, Professor in Zoology at UBC and a long-time colleague and friend, has said, “Don Moerman truly represents what the members of the C. elegans research field aspire to be: passionate, open, collaborative, sharing, and wise.”

A C. elegans symposium in Don’s honor is planned for 2021. The date has yet to be determined.

Story by Nina Maeshima with Bethany Becker

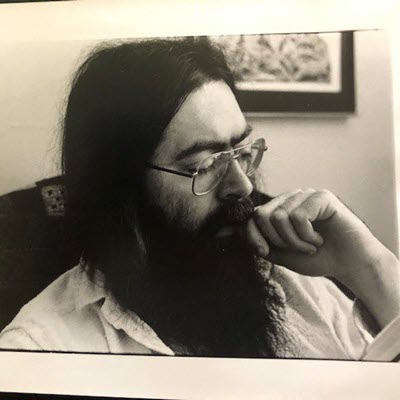

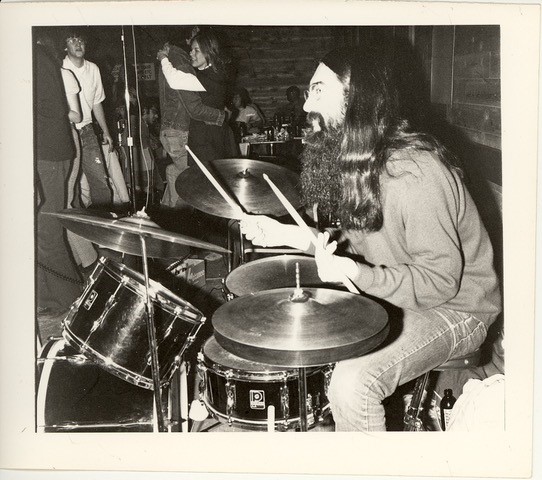

Photos courtesy of Don Moerman and Jan Storer, including an image of Don in St. Louis in the mid-1980s, and photo of Don in about 1972 playing with his band at the SFU pub. He continues to play in a band including fellow musicians Cal Roskelley, Chris Lowen, Kelly McNagny and Dave Rogers, called “The Lost Boyz.”